An Unexpected Technique Brings Artifacts to Life

Light painting is a tricky photographic technique. You may have seen images that use light painting to write someone’s name in the dark or illuminate a campsite, but it has many uses and can come in handy in tough situations, such as on an archaeological dig. On a recent assignment to the mysterious City of the Jaguar in Honduras mysterious City of the Jaguar in Honduras

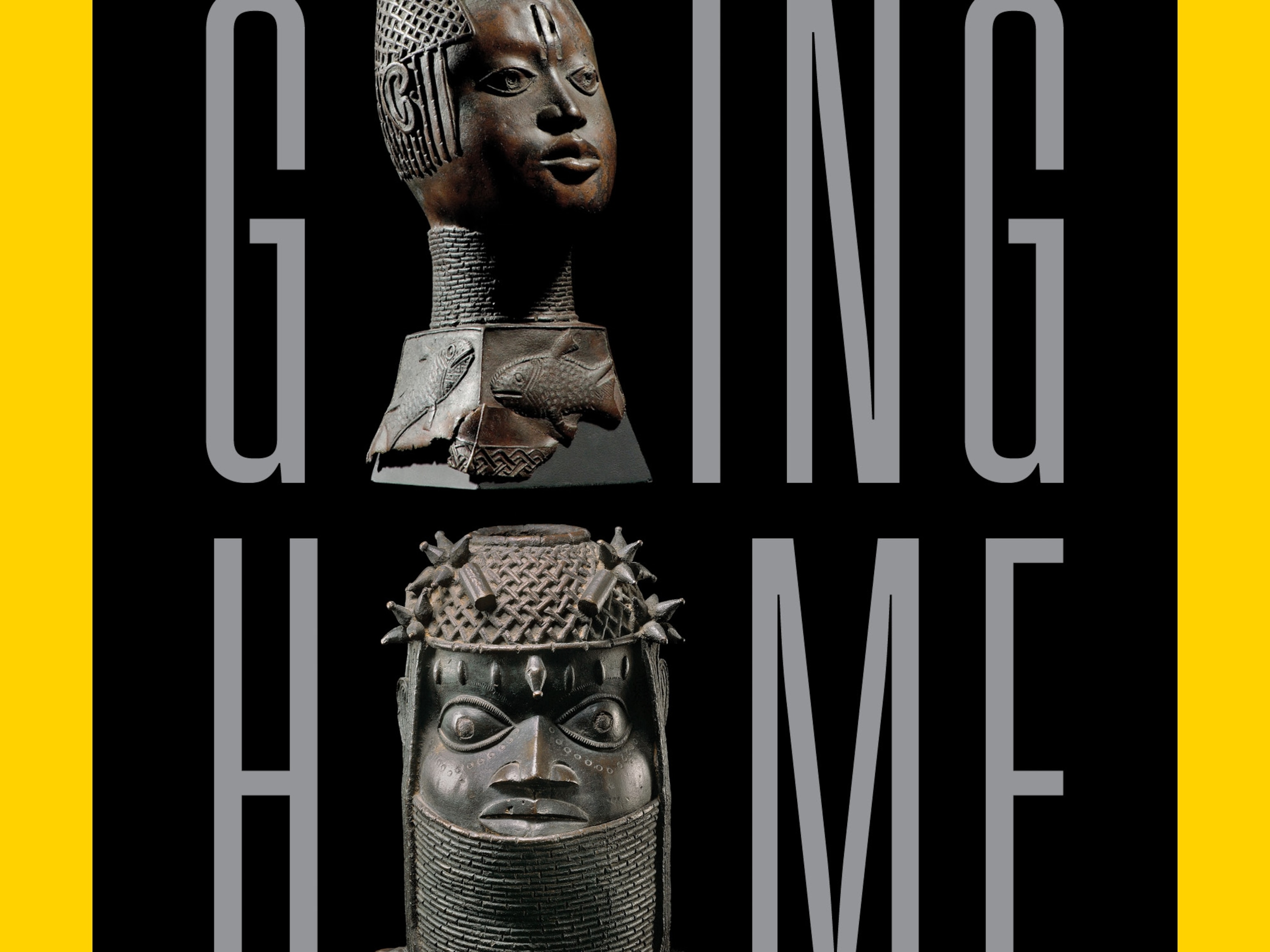

National Geographic

photographer Dave Yoder used light painting to photograph precious artifacts from an untouched ruin.

I don’t have a lot of experience with light painting, so naturally I wanted to get the what, how, and why of using this technique on assignment, and Yoder generously shared his tips, trials, and tribulations with me.

For this high-profile shoot, for instance, the timing was very sensitive, which gave Yoder little time to invent ways to photograph these remarkable ancient objects.

Because the president of Honduras would be visiting and the artifacts would be signed over to the military, it became apparent to Yoder that he would only have a short window to photograph them. “Due to the backlog in cleaning more than 180 artifacts, I had been putting off photographing them until the end of the project,” Yoder says. “Suddenly, I was left with very little time to do so. After talking with my editors from the jungle on a satellite phone, I caught the first chopper out, a Vietnam-era UH-1. On the way back, the wind ripped the sliding door off the chopper, narrowly missing the tail rotor, which would of course have been disastrous had it impacted. But it fluttered away, harmlessly, down into the jungle, a little like a butterfly.”

But Yoder had little time to reflect on this close call with the helicopter—he had pictures to make.

“At the lab I had less than a day to photograph as many artifacts as possible,” he says. “This kind of studio photography isn’t one of my strong points. Photographer Robert Clark, who is a master in this kind of work, generously offered his advice before [I] left, but I realized there was no time to reposition lights for every item. Each item demanded unique lighting due to their diverse shapes, intricate carved etchings, and runes that don’t read well using soft light such as from a soft box.”

It seemed like light painting might be his answer. “Due to time constraints and the demands of the items, I didn’t see a choice. It was daunting—this was only the second time I’ve ever light painted, and I’ve never had any instruction on how to do it.”

Yoder ended up working without the help of his assistants, using an LED light that he had brought for video, along with long exposures to meticulously “paint” each object. The technique helped isolate the artifacts and bring their features to light in a clean, polished way. As Yoder proved in that single day, part of being a

National Geographic

photographer is knowing how to make the most of a tough situation—even if it means learning as you go.Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

Science

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

Travel

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- On the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migrationOn the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migration

- Everything you need to know about Everglades National ParkEverything you need to know about Everglades National Park

- Spend a night at the museum at these 7 spots around the worldSpend a night at the museum at these 7 spots around the world