8 Photos That Inspired Action

This past fall National Geographic photographer Lynn Johnson suggested I do a blog post about photographs that inspired change. I was moved by this idea and thought what better way to end the year than to reflect on the power of a still image. Photographs show us places and things we will never see in person, they express conflict in a visceral and enduring way, and they can be transformative. Photographs can cause us to think differently or move us emotionally, and sometimes they can even propel us into action. I asked eight National Geographic photographers to share examples of how an image or project of theirs that appeared in National Geographic had instigated change. Some of the photographs inspired personal and intimate actions taken by individual readers to help the subjects pictured in the magazine; other photographs and stories resulted in more sweeping, large-scale changes of policy and governmental action. Below is a selection of National Geographic photographs and stories that inspired change over the years. —Jessie Wender, senior photo editor

Curse of the Black Gold

I had not gotten the boy’s name when I made the image, as it was very dangerous for me to be in what is the largest abattoir in the Niger Delta. The workers are suspicious and aggressive to outsiders, especially someone with a camera. Paulinous was 14 in 2006, has five other siblings, and lives in a very poor situation. The working conditions at the Trans Amadi Slaughter, as this abattoir is called, are hellish, and the fact that my image prompted an individual to take such actions reminds me that the power of the still image survives and, more importantly, that people care. —Ed Kashi

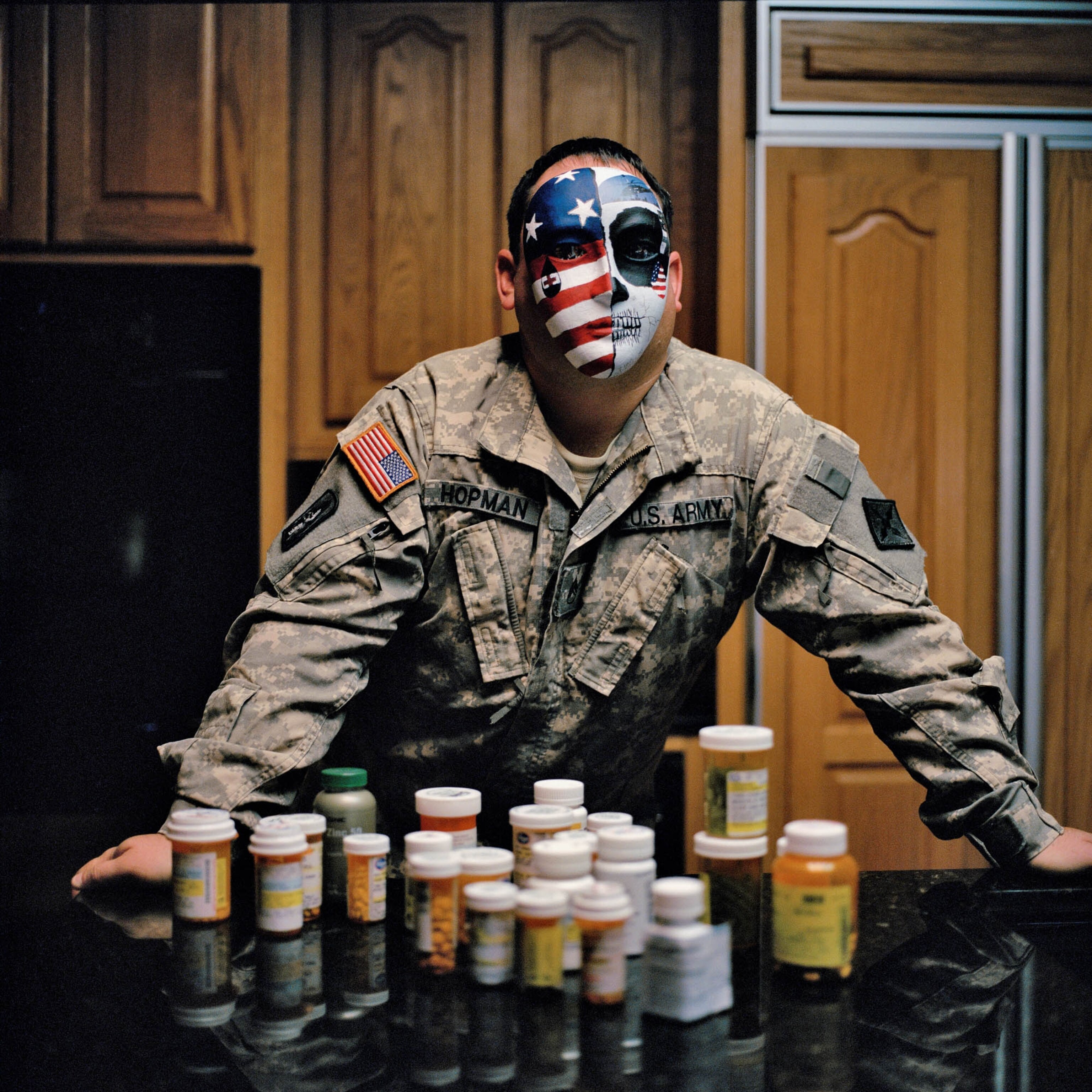

a story about the mystery of blast force injury

And now, months after being photographed in his kitchen with the 22 meds that kept him alive and not quite sane, Perry needed help. He needed a service dog. Perry already had a name for the K-9 that might save his life. But he couldn’t afford to buy or train this unmet savior. A plea for donations, using this image, through the NG Instagram and my colleagues’ websites changed everything. I don’t know the work of every photograph, but I do know the work of this one, and thanks to a photo on tiny screens and readers’ generosity, Perry now has Atlas and hope for a new life. “I feel a sense of security I haven’t felt for years,” he says. “He’s for sure the missing piece of my puzzle.” —Lynn Johnson

In this picture we see a Thai man who calls himself the Elephant Monk. At the time he had more than 250,000 followers. He turned out to be a cunning ivory profiteer, selling ivory amulets to his followers and others and giving journalist Bryan Christy and myself precise instructions on how to smuggle African ivory into Thailand. He was confident his followers in customs would ensure it reached him.

It amazed me that no matter where we looked, so many priests and monks viewed the killing of elephants as a means of deifying God. For them, ivory remains the ultimate substance for carving their devotion, no matter the suffering of these majestic animals and the threat to world heritage.

When this story published it also detailed extensive poaching operations and the routes used for ivory smuggling. Hillary Clinton used it to change State Department policy on the security issues posed by armed poaching gangs. The Vatican denounced the use of ivory for the carving of religious pieces, and a number of priests were excommunicated from the Catholic church. The recent Xi-Obama agreement to ban domestic ivory markets in China also quotes this work and a more recent piece we did connecting ivory to terror groups. Most of the major elephant lobbying that has occurred since 2012 has made extensive use of this investigation and the pictures that came out of it.

This is an uphill battle but one we are committed to fighting. I only wish that more devotees would understand this evil ivory connection and realize that one does not speak to God by slaughtering his creatures. —Brent Stirton

I made several photographs of Eduardo in his grief. I didn’t give him any money. I had no food to offer. I made a few pictures and went away. In our Peru story published months later we ran my picture of Eduardo and it drew the sympathy of many readers. With the thousands of dollars they contributed, his family’s sheep were replaced, a water pump was installed in their village, and the remaining money went to a fund for Andean schoolchildren. My picture of Eduardo didn’t end a war, it didn’t raise millions toward finding a cure to some disease, but it did make a positive difference in the life of one family living in a world away from most of us, where life is not easy. As photographers we tend to be takers. In our rather predatory language we “capture,” we “get,” and we “take.” But every rare once in a while we become givers. That feels so much better. —William Albert Allard

The Price of Precious

Children were being used in the mines and as child soldiers by the various militia. Millions of dollars worth of gold passed over the borders into Uganda every year, and the money to buy more weapons came back. Together with Anneke Van Woudenberg from Human Rights Watch, I used this image to challenge the trading companies and gold industry to halt the illegal purchasing of gold, thereby stopping the funding of armed groups in the region.

Eventually they listened and halted the purchases of gold. The financing diminished, and over time the war came to a conclusion. It was that experience that motivated me to continue the work on natural resource exploitation, and that led me to the North and South Kivus and a decade of work to highlight the exploitation of tin, tantalum, and tungsten. Partnering with the Enough Project among many other NGOs, this eventually led to Intel announcing that all of their processors would be conflict-mineral free and, more importantly, the start of a program to monitor and clean up the supply chain of these minerals in the Congo region.

It all started with this image. That’s the power of photography. —Marcus Bleasdale

a story I did on food insecurity in America

There are a number of brave families who opened their homes and lives to help tell this story. It’s not an easy or comfortable topic to be the subject of, but they valued sharing their story and letting others know they’re not alone. As with most of my stories, I won’t ever know all the ripple effects, but I was very moved to find out that a number of readers reached out to one of the subjects and her family with donations. One let her know she was “inspired” by her story. She inspired me as well. —Amy Toensing

The water that flowed from his bathroom faucet looked like tomato juice that had gone bad. Along with the iron, the water had gray and black chunks that spilled out into the sink, and an oily residue floated on the surface. It smelled foul. I was astounded to learn that for six years he showered in this water and used it to brush his teeth. He was worried about his young sons who drank it.

It is hard to explain the climate of fear and suspicion for some people who live in Coal Country. While working on this story for four years, I’d come to understand the mistrust. People were lied to by politicians. Speaking out about illegal practices could invite intimidation. Neighbors and family members with ties to mining were sometimes pitted against each other.

In this case, employees of a coal processing company in Mingo County admitted that for eight years they injected slurry from an impoundment into underground abandoned mines without a permit. Court records show that as much as 28 million gallons a month of coal slurry that included toxins and heavy metals were dumped into abandoned coal seams that flowed into and polluted nearby wells. Our story about Appalachia did not stop mountaintop removal mining, but it did contribute to the conversation and helped to shed light on some of the shocking practices. Most important of all, our story gave a voice to those who are rarely heard and may have given them hope. —Melissa Farlow

For 15 years, with images published in National Geographic magazine, I documented the Megatransect and Mike’s work on other projects to save the Congo’s forests. He is a man of obsession and singular, unstoppable drive. We are brothers. Today, Mike is back in Gabon, still sacrificing all and working hard to make his dream of those parks and what they stand for a functional reality. —Michael Nichols

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico