Struggling to Survive When the Oysters Have Gone

“We waited about 45 minutes too long, Tyrone,” says Warren Duplesis, the captain of the small flat-bottomed boat we’re riding in, as he eyes the approaching dark gray line on the horizon. After oyster fishing most of the day, the boat is heavy with our catch. The two deckhands pull up the dredge and made sure the bilge motor is working. It isn’t a question of whether we’re going to take on water but of keeping the boat—and its valuable cargo—afloat.

We’re in No Man’s Land, an area between bay Adams and the gulf, about 60 miles southeast of New Orleans. The trip back to the Empire marina was now going to take much longer than the 20-minute trip out that morning. “We are gonna get it,” says Warren as the waves start breaking over our bow.

The darkness of the storm, punctuated by brilliant flashes of lightning, obscures the landmarks, and our group falls in behind a bigger oyster vessel. “Lead us home, Chu Chu,” Warren laughs as one of the crew members of the bigger boat raises his cell phone to photograph us from his warm, dry cabin.

Our engine dies. Warren’s brother, Andrew, tries to change the gas container in the driving rain, but the motor doesn’t restart. The other deckhand, Tyrone Encalade, lashes the boat to one of the others in our small group of three. “This is every day, Tyrone. Every day,” Warren says to me. That’s a lot of perilous every days in his 42 years of oystering.

As we limp back into the harbor, I think about the years I have circled through Plaquemines Parish, this piece of earth and marsh lying on either side of the Mississippi River right before it empties out into the Gulf of Mexico. Every time I’m in New Orleans I feel the pull of these fingers of land at the edge of the sea.

My first extended experience there was in 2004, for a story about the disappearing wetlands of Louisiana. Over the next decade I returned to cover the aftermath of other disasters befalling this fragile ecosystem: Hurricane Katrina’s devastating slice right through the middle of Plaquemines before slamming into the Mississippi Gulf Coast and, in 2010, the BP oil spill that put Plaquemines in the bull’s-eye once again.

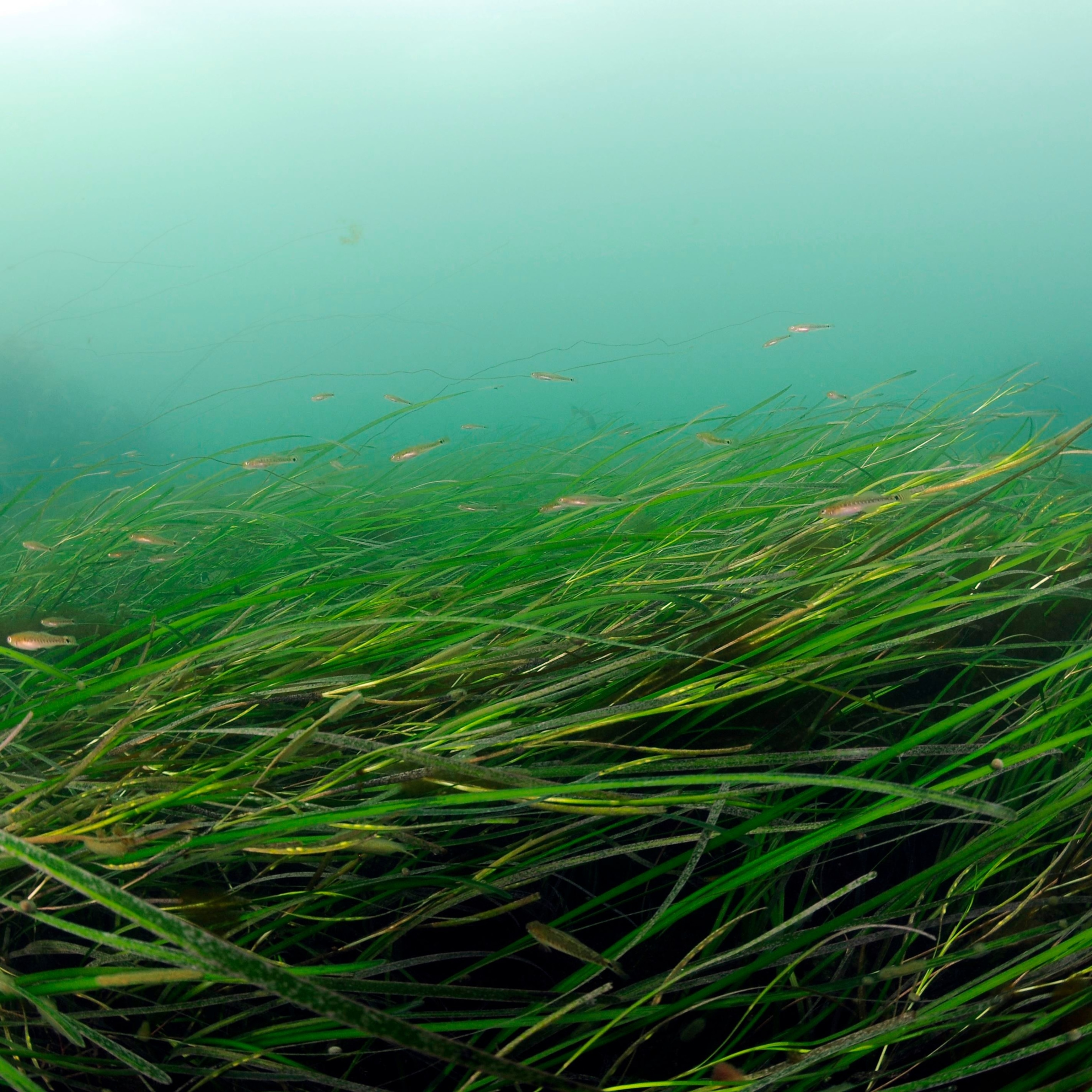

Like all of Louisiana’s coastal wetlands, the land has been formed by deposits from river floods over thousands of years. It’s fertile, but the things that are most harvested are under the ground, such as natural gas and oil, or out in the bayou on the other side of levee systems, such as seafood.

The long-term impact of the oil and dispersants on the marshes and wildlife of the Gulf Coast is still not fully understood. But in the Plaquemines Parish community of Pointe à la Hache, where Warren and the rest of the oyster crew come from, things are not as they were before. Here on the east side of the Mississippi River, where this mostly black and Creole fishing community has traditionally done its fishing, the oysters have not come back in a meaningful way. They now need to travel across the river to the west bank and beyond—and, in the end, make a significantly smaller profit.

Sitting outside a barber shop and barroom across the road from the Mississippi River levee, a gathering place for this quiet community, I talk with one of the other captains from our oyster trip, Myron Tinson. “I never would have thought that Pointe à la Hache would have run out of oysters, not in a million years,” he says after having been a fisherman for four decades.

“The oyster industry was the heartbeat, the soul of the Pointe à la Hache community … and that’s gone … this place [was] recession-proof. But now look at it. It’s a ghost town. Those that could get out, got out. Most of us here, we have nowhere else to go,” says Byron Encalade, the president of the Louisiana Oystermen Association in Pointe à la Hache.

“The destruction that I saw after Katrina was something that fishing communities knew how to deal with,” Byron says. Living in a storm-prone area, they were used to rebuilding houses and boats right afterward. No matter how devastating the hit, the oysters would still be there.

The oil spill was different. “It’s five years and we ain’t even started recovering,” says Byron.

The fishermen of this community have been struggling to survive. Some, like Warren and Myron, travel to the other side of the river to work on oyster boats. Others, like Lennix Battle, have gotten “land” jobs at places like the nearby coal plant to pay bills, though he says he hasn’t had too many shifts lately.

Others still have started hunting. Almost every day, whatever is in season—rabbit, squirrel, duck, pig, deer—Karlan “Peanut” Barthelemy goes out to put food on the table.

I go along on a hunt with Peanut and his friends one day. As we follow the howls of his dogs chasing the scent of rabbit through thick bramble, I keep wary of the muzzle of his 16-gauge shotgun. We can hear other hunters in the party calling out for each other, keeping a safe distance while closing in on their prey.

Shots ring out. “You got him? You hit him?” Peanut shouts. Silence. A rabbit darts like lightning to the side of us. Peanut swings around and I hit the ground. The rabbit gets away. Peanut looks down at me, smiling. “I wasn’t gonna shoot you.”

Later we sit at his dinner table and eat rabbit stew with his six-year-old stepson. “You live off the land; that’s all we can do right now,” he says. “We ain’t got no money to go to town to buy food, put gas in the car. Nobody here’s got no money. They can’t go on no other job and work because they don’t know nothing else but fishing oysters.”

*****

On the go? Download Nat Geo View, National Geographic’s new, bite-size daily digest app for the iPhone. Each day editors select Proof posts, as well as our best pictures, stories, and videos, and send them straight to your iPhone. Check out all National Geographic has to offer in an elegant, easy-to-use app you can tap into wherever you are today.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction