Catching Zombies in the Act: How to Picture Parasites

Photographing a horsehair worm bursting from the body of a drowning cricket is as difficult as it sounds. But it was a challenge that Anand Varma threw himself into for his first National Geographic story.

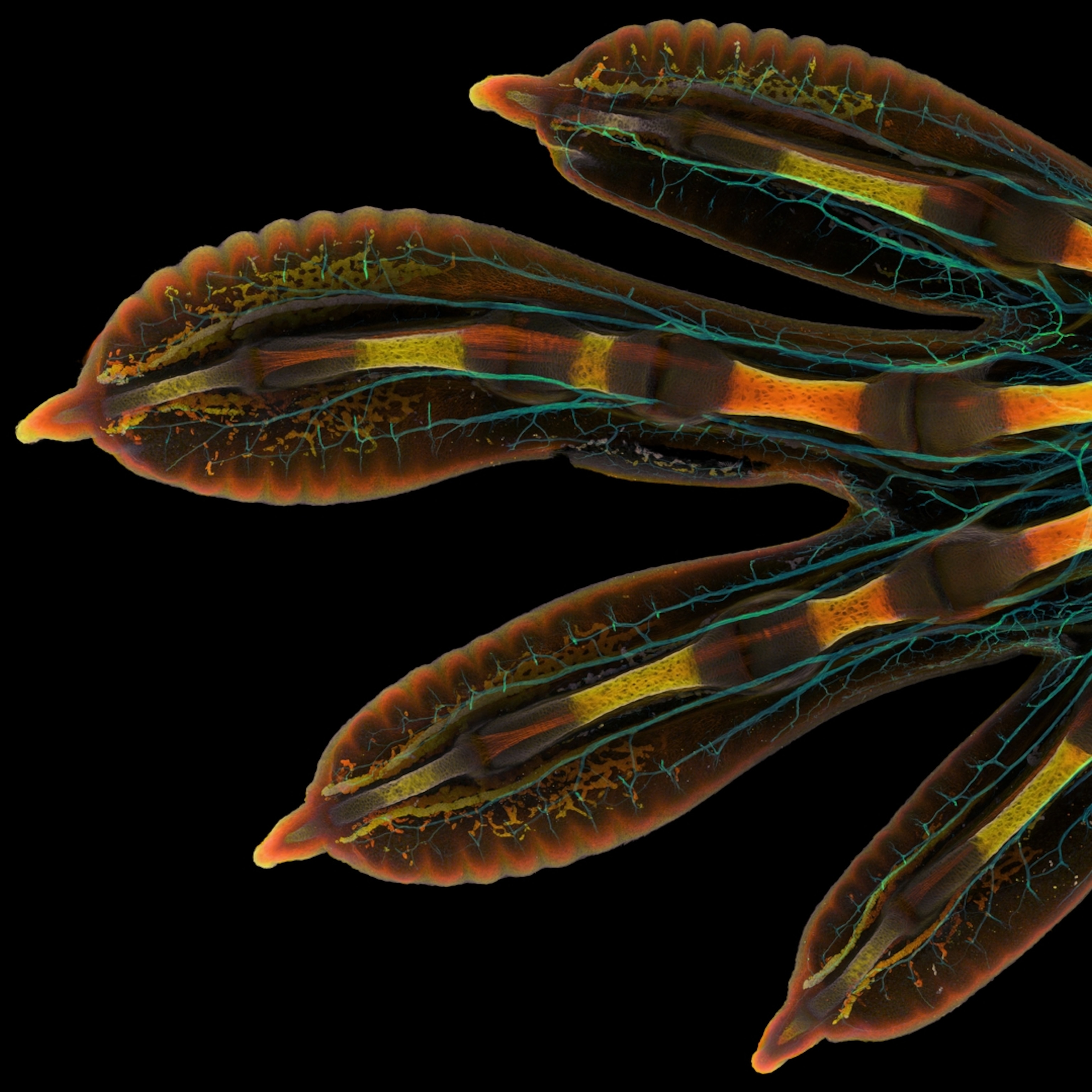

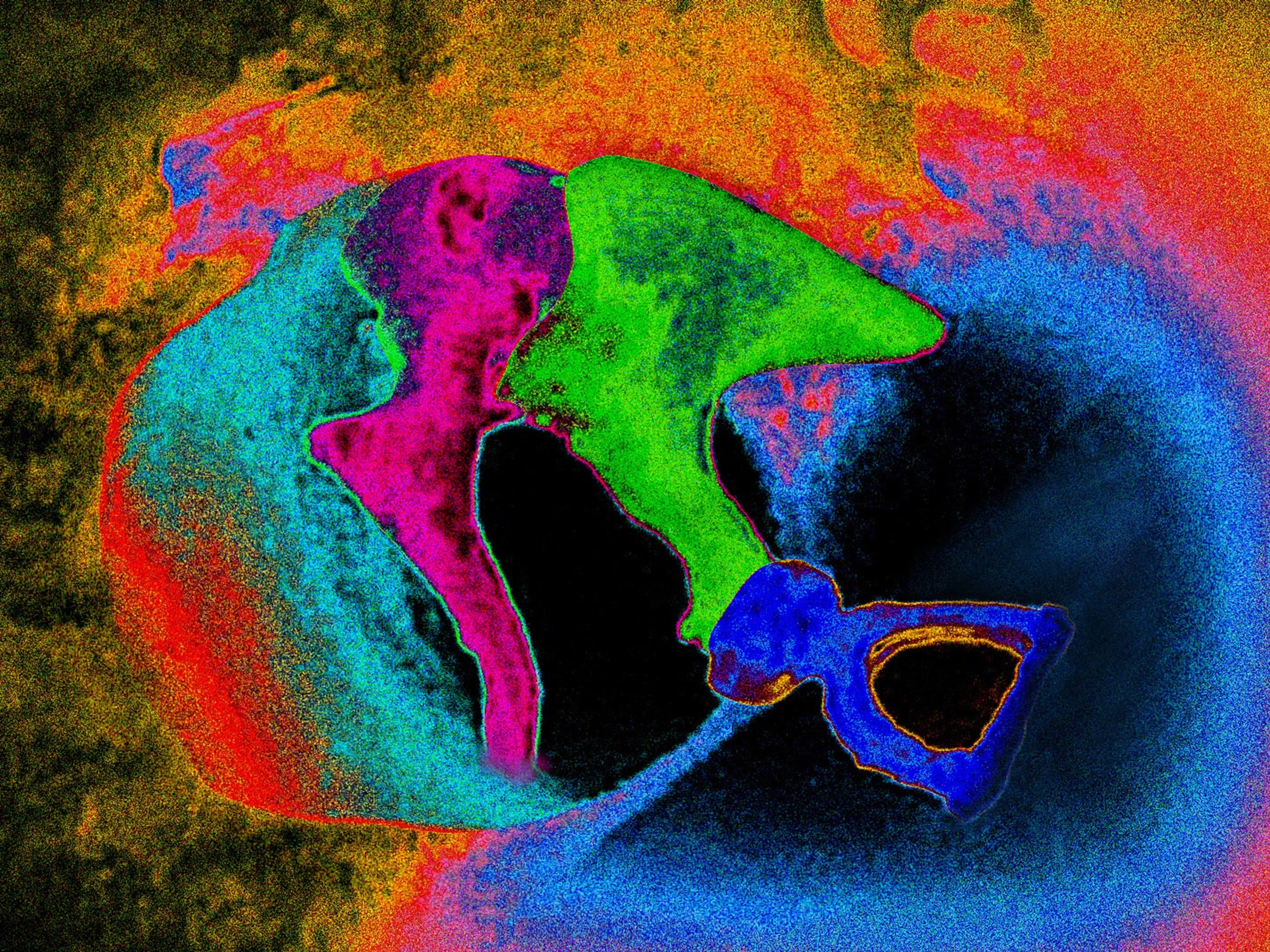

“Mindsuckers” in the November issue is all about parasites that enslave their hosts. These barnacles, fungi, and flatworms invade their host’s brain in order to control their behaviors and to advance to the next stage in the parasitic life cycle.

Varma had been thinking of proposing a story on mind-control parasites to the magazine, but hadn’t fully fleshed out the idea when he met with now retired National Geographic photo editor Susan Welchman in October 2011.

When Welchman asked whether Varma had any projects he was thinking about, he mentioned parasites. Unbeknownst to him, writer Carl Zimmer had proposed a similar story several months prior, and they didn’t have a photographer yet.

“Before I even had a plan about this, [Welchman] was marching me into the director of photography’s office and saying ‘hey, you need to talk to this photographer,'” Varma recalls.

The rest, as they say, is history. Read on to see how Varma caught these zombie-makers in the act and how trying to stay awake late into the night led to an almost noir time-lapse video.

JANE LEE: How do you not gross yourself out when photographing one organism crawling out of another one day after day?

ANAND VARMA: Well, honestly I just think it’s really interesting. I think it’s cool. I don’t start off with the gross factor because it didn’t really feel like such a challenging thing that I had to resolve myself to endure for the sake of my assignment.

JANE: Did you have an interest in parasites before this story?

ANAND: I had heard about a few of these parasites while I was studying as a biology student. They were among many other natural history stories that I thought were generally interesting, but I hadn’t thought much beyond that until one of my classmates went to graduate school to study parasitology. She mentioned that I should do a story on mind-control in parasites. And so I had that kicking around in the back of my mind for a few months. I thought maybe one day I’d propose it to National Geographic.

JANE: Did you know how you wanted to photograph them at the outset?

ANAND: That’s the first thing the director of photography asked: ‘This sounds great, but how would you shoot it, what would it look like?’

[My editor] Todd James set out the constraints: ‘This has really got to look different somehow. You’re going to have to push this in some way. They’re going go straight to story in graphic novel-like illustrations. You have to figure out how to produce photographs that will go with the illustrations.’

The first approach I took was to try and do x-rays. [But] taking an x-ray of [an infected] cricket or crab—there was no way you were going to be able to see the parasite stand out from the host.

I scrapped that idea because even if you knew nothing about biology or how to ID insects or worms, it had to be clear that there were two creatures in the photograph and that there was something weird going on.

The day before I went to New Mexico to photograph [crickets infected with horsehair worms], I went to a comic book store and looked at the covers. What does it mean to be a graphic novel?

The unifying theme that I see is that they’re all using background. The background of the image is key to communicating where the action is, where the drama is.

How do I use light to get across the idea that there are two creatures interacting here? And how do I use background to help me tell that story?

JANE: How did you come up with the time-lapse video?

ANAND: I had a proof of concept grant [where] I photographed the crabs and crickets. Since my editor didn’t have time to look through all my pictures, I was trying to edit [the images] down. It was late at night, I was scrolling through images and listening to this dubstep music just to keep myself awake, and that’s where I got this idea.

I just exported this video and set it to music more as a joke than anything.

The video evolved to give an overview about how the parasite and host interacted, the worms come out, the larvae is spinning a cocoon. You get a sense of the natural history and of the creative process from my end.

(See the full gallery of unwitting hosts and their wily mind-controllers.)

JANE: What kind of reaction have you been getting to this story?

ANAND: The most common phrase I hear is “that is really gross, but that is really cool.” In a lot of ways, that’s a really rewarding thing to hear because there’s plenty of biologists that I’ve worked with or shared this with and they say, that’s really cool. But it’s when someone I’m pretty convinced would never have been interested in that story before—I take pride in giving parasites a fresh face in a sense.

JANE: What do you think is the most dramatic thing about parasites?

ANAND: [They] turn our assumptions about the order of life on their head. To learn about what I would have thought of as a blob of goo outwitting another species far more complex—it just sort of points to how complex and interesting the world really is.

Join Anand Varma for a live Facebook Chat on Thursday, November 6, 12pm EST (5pm UTC). Varma will be talking about getting up close and personal with tiny creatures for the Macro Assignment currently running in Your Shot, our online photography community.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

Science

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

Travel

- How to plan an epic summer trip to a national parkHow to plan an epic summer trip to a national park

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads